In the current football-lite landscape, reflecting on the past is en vogue like never before. Recent discourse has seemingly focused on who was deserving, and who wasn’t, of that shiny beacon of individuality that so many modern players crave, the Ballon d'Or.

There is an Anglo-centric, or perhaps a more Arsenal-centric view, that Thierry Henry was somehow robbed of winning the Ballon d’Or in the earliest part of the 2000s. The pro-Henry camp duly acknowledges that because of tournament-bias, the 2002 award was rightfully Ronaldo’s, as was Fabio Cannavaro’s four years later. Furthermore, Ronaldinho’s 2005 win doesn’t seem to be up for debate given that he was indisputably the greatest player on the planet. No, the prevailing rhetoric seemingly centres on 2003 and 2004. It is then they believe the greater miscarriage of justice was committed.

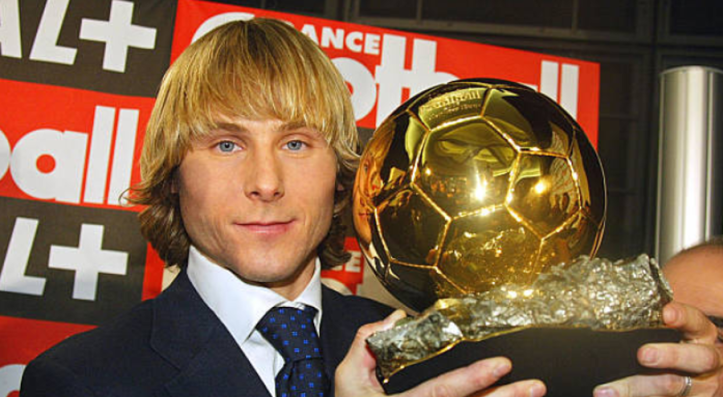

An element of snobbery creeps in here; the pro-Henry camp is almost affronted by the fact that the winners of the award in those years, Pavel Nedved and Andriy Shevchenko, finished ahead of the Frenchman. This is despite the fact that the pair are two of the finest players ever to emerge from Eastern Europe, but are perhaps not considered all-time greats compared to Cannavaro, Ronaldo and Ronaldinho.

Henry came closest in 2003, when he finished second on the podium behind Nedved, losing out by some 62 points. The stick to bait the Czech with is his mundane stats compared to Henry’s in 2002/03. Let’s be clear, Henry’s statistics that season border on the simply ludicrous: 24 goals and 20 assists from 37 league games is barely plausible, in fact it’s never been repeated in the Premier League. Henry was involved in over 50% of the Gunners’ 85 league goals that season as they finished second behind Manchester United which is an astounding figure.

Yet a direct comparison between Henry and Nedved isn’t viable given how they operated in different roles. Nedved’s stats don’t even come close to matching Henry’s in 02/03, but the measuring stick for winning the Ballon d’Or in non-tournament years - particularly in this era - was the Champions League, and it’s here where Nedved trumps Henry.

Nedved had been deployed as a left midfielder in his first season at Juventus, but was shifted to play behind strikers David Trezeguet and Alessandro Del Piero in 2002/03. This brought out the best in Nedved, who saved his finest performances for Europe’s grandest nights. He was involved in two of Juve’s three goals against Barcelona at the quarter-final stage, netting a crucial away goal with the tie delicately poised at the Camp Nou.

Nedved’s performance against Real Madrid in the semi-final second leg is the game that effectively cemented his Ballon d’Or win. Madrid, then at the high point of the first Galactico era, and just before the balance of the side became erratically skewed, were torn to pieces by Nedved’s relentless running and ability to ghost in behind the lines.

Again, he was involved in two of Juve’s three strikes that night, including his stunning volley in the 73rd minute that was the piece de resistance of an emphatic individual display. Nedved’s seminal performance was the sort that Henry simply never produced in Europe for Arsenal that season, or in any during his eight-year stint in north London. Henry scored seven times in the Champions League that season, but Arsenal failed to go beyond the second group stage.

The modern-day appraisal of Shevchenko is viewed through the prism of his spell in the Premier League with Chelsea. Nine league goals in two problematic seasons when he was past his prime and struggling for fitness has given license for many to pour scorn over his Ballon d’Or win.

The call for Henry to be awarded the 2004 title is underpinned by his pivotal role in ‘The Invincibles’ side that won the league without losing a single game. Henry was undoubtedly at his swashbuckling best in 2003-04, scoring 30 goals and providing nine assists in the Premier League.

The Ukrainian, in contrast, rattled in 24 goals in 32 Serie A games as Milan won the title for the first time in five years. This was at a time when the sheen hadn’t completely worn off Serie A’s global reputation, and in the post-Gabriel Batistuta landscape, Shevchenko was unquestionably Europe’s deadliest striker.

BALLON D'OR PAST WINNERS

Ballon d'Or in Henry era

| # | Year | Winner | Club | |

| 1994 | Hristo Stoichkov | Barcelona | ||

| 1995 | George Weah | Milan | ||

| 1996 | Matthias Sammer | Dortmund | ||

| 1997 | Ronaldo | Inter | ||

| 1998 | Zinedine Zidane | Juventus | ||

| 1999 | Rivaldo | Barcelona | ||

| 2000 | Luis Fugo | Real Madrid | ||

| 2001 | Michael Owen | Liverpool | ||

| 2002 | Ronaldo | Real Madrid | ||

| 2003 | Pavel Nedved | Juventus | ||

| 2004 | Andriy Shevchenko | Milan | ||

| 2005 | Ronaldinho | Barcelona | ||

| 2006 | Facio Cannavaro | Real Madrid | ||

| 2007 | Kaka | Milan | ||

| 2008 | Cristiano Ronaldo | Man Utd | ||

| 2009 | Lionel Messi | Barcelona | ||

| 2010 | Lionel Messi | Barcelona | ||

| 2011 | Lionel Messi | Barcelona | ||

| 2012 | Lionel Messi | Barcelona | ||

| 2013 | Cristiano Ronaldo | Real Madrid | ||

| 2014 | Cristiano Ronaldo | Real Madrid |

“Shevchenko didn’t win more, didn’t score more goals, and contributed less in assists,” objected the impartial Arsene Wenger in the wake of the Shevchenko’s victory. That might be statistically true, but again, with Europe being the barometer, Henry falls short. It’s not just how many goals you score, but also when you score them.

Both Arsenal and Milan exited the Champions League at the same stage in 2003-04 - the quarter-finals - but Shevchenko scored more goals in the knockout rounds than Henry (three to two). Furthermore, in the four-year period from 2002-06, when both were contesting for the Ballon d’Or regularly, Henry only scored five times from 13 games in the knockout rounds, compared to Shevchenko’s 11 in 20.

Wenger is of the opinion that due to being French and France Football being the creators of the prize, Henry was held to a much higher standard than the eventual winners (Wenger of course conveniently forgetting that the award is voted for by journalists across the world, and not handpicked by the magazine). Yet the simple fact is that despite being one of the world’s best during the early-to-mid ‘00s, he was never the best.

Henry’s inability to transfer his league form into Europe (or for France, for that matter) is what ultimately denied him a Ballon d’Or. Henry never stamped his authority on a high-end European night in the manner Nedved did in 2003, or continually score in crunch knockout games like Shevchenko. Kaka, for example, won the 2007 award for essentially playing extraordinarily well in a handful of games, all of which happened to be in Europe.

So, in the end, was Henry wrongfully denied a Ballon d’Or? The answer is no.

Lionel Messi

Lionel Messi  Cristiano Ronaldo

Cristiano Ronaldo  Arsenal

Arsenal  Milan

Milan  Juventus

Juventus  Man Utd

Man Utd  Real Madrid

Real Madrid  Barcelona

Barcelona  Inter

Inter  BVB

BVB  Bayern

Bayern